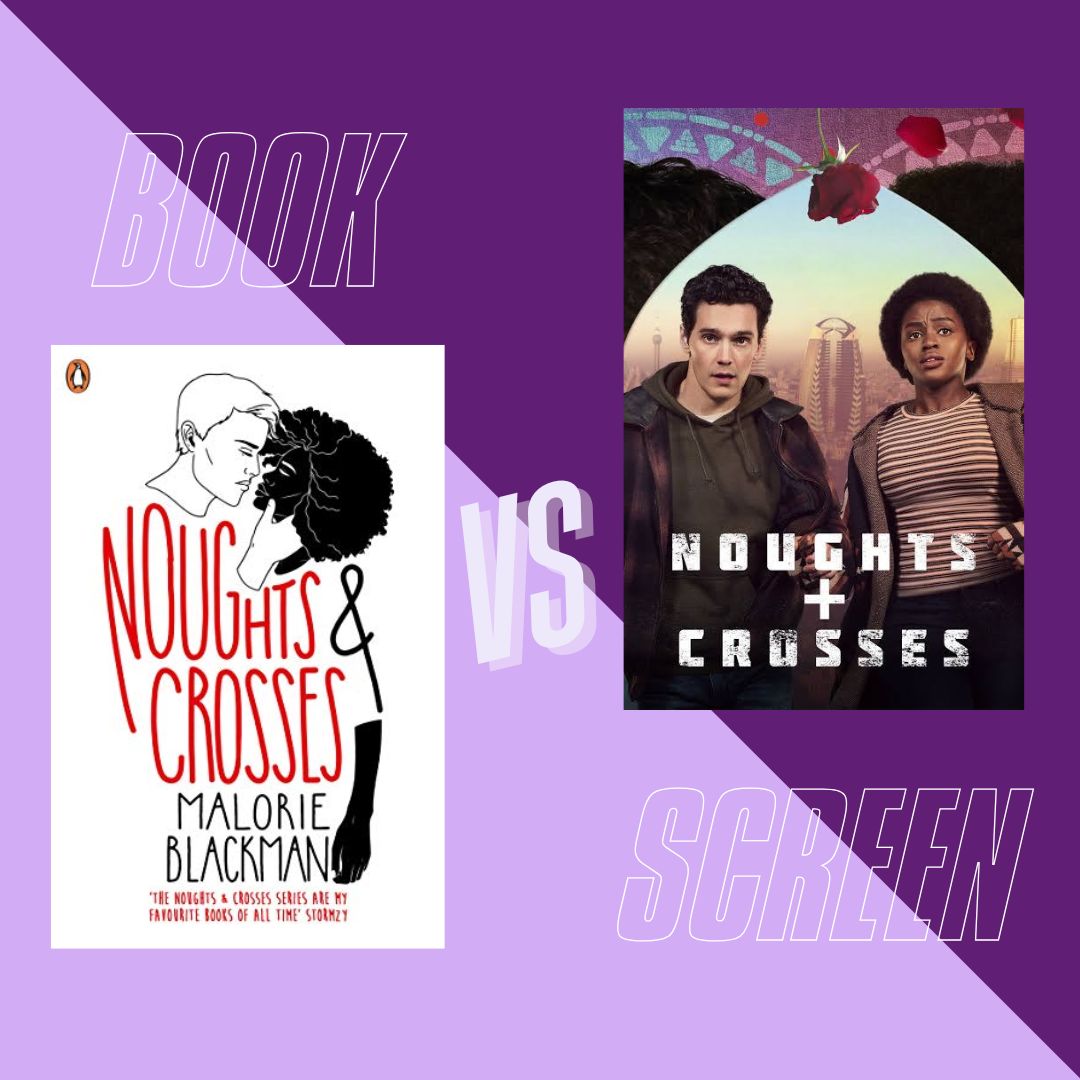

Noughts and Crosses by Malorie Blackman

Book Published: 2001 | Show Released: 2020 Genre: Young Adult Dystopian Fiction

This post is probably one of the more challenging ones I’ve written in a while, and for two main reasons. In keeping with Black History, specifically Black British history, I wanted to focus on Black stories that have been adapted for film or television. There are a few, not particularly mainstream, but they do exist.

The second challenge was determining whether I had actually read the book and watched the adaptation, and if I had time to, if the answer was no. Luckily, the answer to that question is Noughts & Crosses, the one Black British book-to-screen adaptation I’ve both read and watched. It certainly helps that this is a story I am very familiar with, and as I mentioned in my teen favourites post, one I absolutely love.

The difficulty, however, is that I read the book over ten years ago and watched the series almost five years ago, when it first aired on the BBC in 2020. As a result, my memory of both is rather hazy. I had to do quite a bit of research — reading recaps, book reviews, and summaries — mostly to refresh my memory of the show rather than the book.

I remember really enjoying the novel as a teenager and still recall many of the major moments, but when comparing the book vs screen adaptation, you need to keep both the small and significant details in mind. Despite the time gap, I was determined to discuss this adaptation properly, so I made sure to put as much effort into this post as possible. That said, this will be more of an overview comparison than a deeply personal one, as many of my other book vs screen posts have been.

Synopsis

Two young people are forced to make a stand in this thought-provoking look at racism and prejudice in an alternate society.

Sephy is a Cross, a member of the dark-skinned ruling class. Callum is a Nought, a “colourless” member of the underclass who were once slaves to the Crosses. The two have been friends since early childhood, but that’s as far as it can go. In their world, Noughts and Crosses simply don’t mix. Against a background of prejudice and distrust, intensely highlighted by violent terrorist activity, a romance builds between Sephy and Callum — a romance that is to lead both of them into terrible danger.

Adaptation Context

To my knowledge, this adaptation is the first Black British young adult novel to be brought to the screen, which makes it a particularly significant milestone for Black British storytelling. It aired on the BBC and was also made available on Peacock for international audiences.

I do think the series would have benefited from a slightly higher budget. Even so, what the creative team achieved with the resources they had is genuinely impressive. The world they built feels both familiar and distinct, recognisable in its modern Britishness, yet strikingly reimagined through an Afro-futuristic lens that feels entirely its own. The casting choices were strong across the board, with particularly compelling performances from the leads.

Setting and Worldbuilding

The book is set in a society that feels slightly older but still recognisable to today’s readers. Released in 2001, it reflects much of what life looked like in the 1990s and early 2000s, a world of early mobile phones, dated social attitudes, and pre-social media dynamics. The television adaptation, on the other hand, adopts an Afro-futuristic aesthetic that feels bold and visually striking. It’s hard not to see the influence of Black Panther and the profound cultural shift that the film inspired in how Black identity and creativity are represented on screen.

The story unfolds in an alternative present-day Britain known as Albion. In this version of history, a West African empire called “Aprica” colonised Europe. The result is a society deeply infused with African influence, particularly from West and Southern Africa, visible in its fashion, architecture, language, and hairstyles. Yoruba culture (from Nigeria) is especially prominent, with the fictional language and design elements drawing clear inspiration from it.

Visually, the show’s setting is bright and vibrant, a world that showcases the richness and beauty of African and Black British culture. What I particularly loved was seeing Blackness represented in every aspect of life, from government and media to everyday social spaces — a refreshing reversal of what we typically see in contemporary Britain. Yet, this very portrayal also underscores the systemic nature of racism and oppression in our real world, making the viewer acutely aware of the structures and inequalities that persist.

Romantic Focus

For me, one of the biggest differences between the book and the screen adaptation lies in the portrayal of Sephy and Callum’s romance. In the novel, their relationship begins when they are much younger and unfolds gradually over several years. This long-term development makes their connection the emotional core of the story, with everything else — politics, family tensions, and societal conflict — orbiting around it. It’s very much a modern Romeo and Juliet scenario: a deeply forbidden love that feels both tender and tragic.

We’re drawn close to Sephy and Callum, and their love feels profound and rooted in years of shared history. The book offers far more introspection and emotional depth, exploring in detail the difficulty of maintaining love within a world built on prejudice and inequality. Romance is often a great prism for exploring and critiquing society. Callum’s struggle to reconcile his feelings for Sephy with the reality of the oppressive system she belongs to is particularly poignant and well-developed.

“Love was like an avalanche, with Sephy and I hand-in-hand racing like hell to get out of it’s way-only, instead of running away from it, we kept running straight towards it.”

malorie blackman

In contrast, the show places greater emphasis on the political landscape of Albion and less on the romance itself. I’ll explore the thematic elements a bit later, but while the political narrative is powerful and essential, the shift in focus means the romantic thread becomes secondary. The series is driven by politics first and love second, and while that isn’t necessarily a flaw, it does affect how invested we feel in Sephy and Callum’s relationship. Because they are aged up in the adaptation, we miss those formative early years of friendship and emotional build-up.

As a result, their romance feels somewhat underdeveloped — almost as if it appears suddenly, without the gradual foundation that made it so believable in the book. This makes Callum’s internal conflict less convincing; we see that he loves Sephy, but we don’t fully understand why or how that love became strong enough to create such turmoil within him.

Plot Adjustments

As I mentioned earlier, several adjustments were made to ensure the plot worked effectively for the television adaptation. The original book is a young adult novel aimed at readers aged around 13 to 16, whereas the series was clearly designed to appeal to an older audience, reflected in its 9 pm broadcast slot. As a result, a number of changes were made to make the story more mature and suitable for that audience.

Both Sephy and Callum were aged up to around 18, positioned as young adults rather than teenagers, whereas in the book, they begin at about 14. This alteration significantly changes the dynamic of their relationship, as well as how the story unfolds. For instance, Callum’s involvement in the military academy and the challenges he faces there serve to maintain the book’s core focus on racial tension and systemic oppression, albeit through a different lens.

We also lose key characters, such as Callum’s sister Lynette, who plays a crucial role in shaping his worldview and influencing his decision to join the Liberation Militia.

The most significant change, though, comes at the end. Without giving away any spoilers for those who haven’t read the book, the series concludes quite differently, avoiding the dramatic shift that defines the book’s finale.

Themes

The themes of the story, and seeing them play out on screen, are the most striking part of the adaptation. Much of the violence in the book is implied rather than shown, whereas the series presents it in far more graphic detail. A palpable sense of danger runs throughout Noughts and Crosses, established from the tense opening scene and sustained by its formidable antagonists.

On one side, there is Sephy’s current boyfriend, Lekan, whose deep-seated insecurities make him both paranoid and dangerously unpredictable. On the other hand, we have Callum’s volatile brother, Jude, whose simmering rage against the Cross regime draws him towards increasingly destructive influences. Overseeing it all is Sephy’s father, Kamal Hadley, a high-ranking politician whose power and manipulation loom large over the story. His calculating political manoeuvres are genuinely menacing.

Reversal of Power and Social Hierarchy

The central concept, a world where Black Crosses hold power over white Noughts, forces readers and viewers to confront systemic racism from an inverted perspective. Many of the negative reactions to the show stem from discomfort at seeing white characters in demeaning situations rarely depicted in today’s society. This inversion challenges audiences to recognise how deeply racism is embedded in social structures, law, and everyday life. The message is portrayed effectively in both the book and the series.

Systemic Discrimination

The book explores segregation and how discrimination is woven into every aspect of daily life — the opportunities afforded to the ruling class that poorer and minority groups cannot access, the lack of political representation, discriminatory employment practices, and the enforced assimilation that erodes culture and individuality. Seeing white people conform to Black hairstyles is almost shocking in a world where white people are often celebrated for the very things for which Black people, especially women, are criticised. The TV series visualises these injustices vividly through strong imagery, from police brutality to the policing of Nought identity.

Violence and Resistance

The Liberation Militia storyline reflects how oppressed groups often resort to radical measures when peaceful routes fail. It powerfully represents the idea of meeting violence with violence, one of the few ways oppressed groups are ever taken seriously, though they are rarely granted the same understanding when it comes to resistance. The show amplifies this political struggle, portraying resistance as both necessary and morally complex. Telling an oppressed group how to respond to or accept their oppression remains an ongoing and uncomfortable conversation within society. This is especially resonant now, especially with the genocide happening in Gaza today.

Critique

For dramatic effect, the series draws on different eras and expressions of racism, which at times makes its approach feel uneven. Some of the racism depicted is overt and recognisable, yet it overlooks the more insidious, covert prejudice that defines much of modern society. By focusing so heavily on visible acts of violence, the adaptation misses the chance to explore the subtler, more psychological forms of oppression that could have made it even more powerful.

Blackman’s story offers a sharp commentary on representation and power, but the adaptation doesn’t always trust its audience to interpret these ideas independently. As a result, the themes can feel heavy-handed and overly direct. While emphasising certain points helps drive the message home, the lack of nuance occasionally weakens its overall impact — perhaps a symptom of adapting a young adult novel for an adult audience.

Final Thoughts

Overall, I think it remains a solid adaptation, capturing the very best parts of the book and its core message. The show continues into a second season, which I haven’t seen, but judging by how the first ended, I doubt it will extend much further into Sephy’s story (no spoilers, of course!). That said, I still believe it was a strong and enjoyable attempt — a beautiful way to tell and portray an experience we know all too well.

I’m also glad that Malorie Blackman was involved every step of the way; this is an adaptation she feels represents her “baby” faithfully. It was wonderful to see such an array of Black faces on screen telling a distinctly Black British story, and for that reason, the series will always hold a special place for me.

This ended up being quite long, haha – I didn’t expect that, but there was quite a lot to get through! I hope you enjoyed this post and are enjoying Black British History as told on In Novel Company.

Do stick around and explore some of my other posts, and I’ll see you next week!

Signed,